After a year’s delay, the Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games have begun. Met with challenges from the COVID-19 coronavirus and negative public opinion domestically, pushing ahead with the Games this summer is a controversial decision, so it is understandably harder to feel excited about the Games as it would be if they were held without concerns about an ongoing pandemic.

The Olympic Rings at the Odaiba Marine Park. (Image courtesy of Erik Zünder via Unsplash)

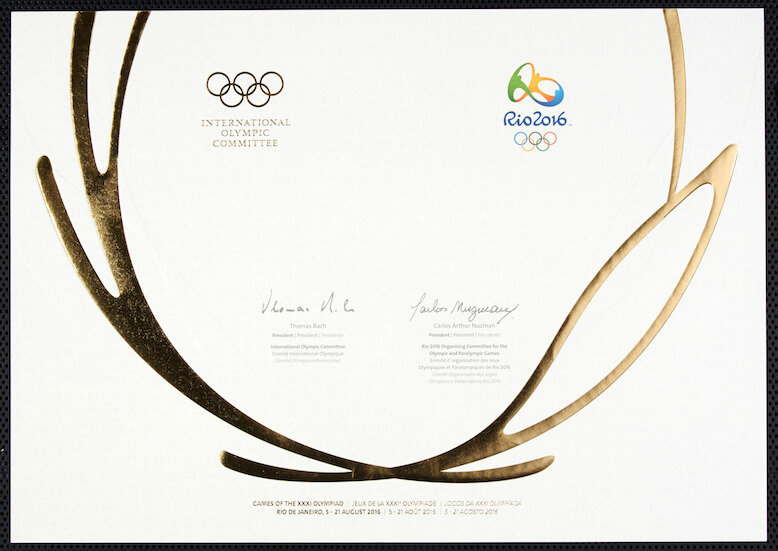

However, the split opinions on whether or not the Games should be held does not change how athletes worldwide have put in a tremendous amount of work to earn their places at one of the world’s most prominent sporting events. Most of us are familiar with the scene where the top three winners take their steps up the podium to receive their medals, but did you know that athletes ranking up to eighth place for the Olympics receive a Victory Diploma?